Upon my return from vacation in late March, I met some friends for chicken and beer. When I gave the bar attendant 500 CFA (about $1 USD) to pay for my beer, he told me that the price has changed, a beer is now 600 CFA (about $1.20 USD)! While readers in the developed world snicker at a seemingly nominal price increase, I would like to point out that it is a 20% increase. To compare it to a U.S. tax increase of the same percentage would be flippant, but that doesn’t mean it will not have an impact on Cameroonian life.

There had been rumors of this tax being initiated by the government in December, but I heard later it had been stopped to appease the brasseries. After the tax took effect, I heard through the grapevine that BBC interviewed bewildered people in Bamenda who said they would just drink more palm wine (which is not being taxed). Taking this into consideration I want to consider whether this new tax will be a good idea for the Cameroonian economy.

The alcohol tax is a consumption tax, which is often implemented to tax things the government wants to incentivize. Because the government wants to affect a very specific category within consumption, the levy is called an excise tax. In this case, the Cameroonian government wants to discourage people from excessive drinking by raising the price; for the government, it is a win-win because even if people to do not reduce consumption, it will still increase revenue.

One of the perceived benefits of this alcohol tax is that it is only affecting a nonessential good. No one needs beer—beer is a luxury! Therefore the tax is not attacking the poor. In terms of revenue growth, the tax has its limits. The Gross National Income for a Cameroonian is about $1,290 per year or $3.50 per day. A full 39.9% of Cameroonians are living below the international poverty level according to the World Bank. In addition to a limited income, where one beer is a significant percentage of the daily income, there is the marginal utility factor: the first beer provides more happiness or satisfaction than the second one, each beer after the first is less wonderful than the previous one. In other words, there is not the potential for infinite consumption of beers.

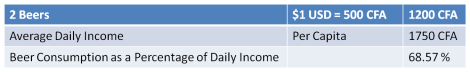

**I realize that the table below looks like it is making the assumption that each person consumes the average number of beers each day, but this table is designed to illustrate that a price change of 20% can affect the budget of Cameroonians.

Elasticity. Elasticity is the degree to which individuals change their demand/amount supplied in response to price of income changed. Considering the human factor in this excise, the Cameroonian income did not shift to accommodate the increase in the price of alcohol, so for a person to continue drinking the same amount, they would have to take money from another category within their budget (food, school fees, rent).

Public drinking in Cameroon is usually very male dominated, it’s not that women don’t drink, but they are in the house most of the time—it’s a bit taboo for women to be drinking in public especially in villages. Because of this, when discussing drinking it will be from a male perspective since that is where I get most of my information. It’s estimated by my friend Ben that when a man sits down to drink, he will take an average of 2-3 beers; but if it is cocoa season, he will increase his intake to 5-7 beers easily. That is an elastic response to an increase in income. So from this we know that beer could be classified as very elastic. Going back to the tax, we should consider whether the 20% tax will affect the number of beers sold because it is an elastic good. If the price increase is following economic law, then yes, total consumption will decrease as the price increases.

Other things not often considered that are specific to Cameroon:

A factor that might hamper the revenue of the alcohol tax is the availability of alternatives. There are these things called “sachets” here, they are like little sealed envelopes of alcohol (mostly ethanol) that cost 100 CFA, they are purported to have doubled to 200 CFA, but still costs much less than a beer. They are popular with people needing to drink “on the go”, so motorcycle drivers, bus drivers and so on. In other words, these are for alcoholics who must work. People working in transport are also some of the people shouldering a lot if income instability so the price is right. And yes, drinking and driving is deadly. My very unscientific observation tells me they appeal to those who might not be able to afford a beer. So I’m not convinced the alcohol tax will chip away at any sort of public health alcoholism issue.

On the finance side, we go back to the question of what will Cameroon do with all of it’s new revenue? Well, we might never know. Corruption is an issue that reaches every facet of life here and it’s possible those new funds will be “diverted” away from the original purposes designated by officials speaking to the press.

Cameroon is also home to a sizable Muslim population, mostly concentrated North of the Adamawa, and down through to Foumban, that means there isn’t a whole lot of drinking (or at least reduced) in much of the country. It also means this tax will really only affect Christians.

I’ve read multiple conflicting accounts online of the purpose of this tax ranging from funding HIV/AIDS care, paying for the harm caused by alcohol (I derive “public health” from that), and even funding public service coffers. Either way, I see this tax as a pretty good idea. Collecting income tax form Cameroonians can be very difficult because of the sheer size of the informal market. To raise revenue, you should tax something that is close to their hearts, beer. Yes, it’s elastic but after some foot stomping things appear to be back to business as usual here.